By Peng Zhao | April 6, 2019

- What Will I Learn?

- What the R ‘pinyin’ package can do for you

- How to Set up the environment which ‘pinyin’ requires.

- How to use the main functions of ‘pinyin’

- Requirements

- Windows/mac/Linux OS

- R environment

- R pinyin package

- RStudio IDE (recommended)

- Difficulty

- Basic

What is ‘pinyin’

‘pinyin’ is an R package for converting Chinese characters into pinyin, four-corner codes, five-stroke codes, and more.

You might wonder: what the hell are them?

Chinese people type “中文字符” with a normal computer keyboard. How do they do it? The answer is Chinese input methods, such as pinyin or five-stroke codes.

Pinyin is the official Romanization system for Standard Chinese in many countries and regions, including the mainland China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, etc.. Pinyin system includes four diacritics denoting tones. Pinyin without tone marks (toneless) is used to spell Chinese names and words in languages written with the Latin alphabet, and also in certain computer input methods to enter Chinese characters. More details could be found in Wikipedia.

If you don’t get it, don’t worry. Here is an example: if you type ‘zhongwenzifu’ with a Chinese input method in your computer/cellphone, you get ‘中文字符’, which is pronounced zhongwenzifu. Try it here.

Thus, pinyin is not only an input method, but also a system showing the pronunciations of Chinese characters with Latin letters.

Then what is four-corner codes?

The Four-Corner system is a character-input method used for encoding Chinese characters into either a computer or a manual typewriter, using four or five numerical digits per character. In another word, it is an alternative system of pinyin. For more details, see WikiPedia.

Another alternation is the five-stroke system, or Wubizixing input method. It is often abbreviated to simply Wubi or Wubi Xing.

The R ‘pinyin’ package works basically as a free translator for Chinese characters. If you have learnt how to use it, you could definitely do more than expected.

Set up the environment

Before using ‘pinyin’, the R language must be installed. R is a free, open-source, cross-platform programming language, which is very friendly to non-professional programmers. The installation of R can be found on the official website of the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) or in many textbooks such as Learning R: R for Rookies. For the tutorial’s integrity, here is a brief description for Windows users. Mac and Linux users can simply follow the official manual by CRAN.

- Go to CRAN. Click the right link in the list of ‘Download and Install R’ according to your platform. Here we click ‘Download R for Windows’.

- Click ‘base’.

- Click ‘Download R 3.5.3 for Windows’, which is the newest version of R. It could be updated in the future.

- Double click ‘R-3.5.3-win.exe’ and click the ‘Next…’ button to complete the installation.

The default R editor is primitive. We highly recommend the users to use a third-party editor, such as the free, cross-platform editor RStudio IDE. Just go to the download webpage of RStudio, and click the download link according to your platform. Here we download ‘RStudio 1.1.463 - Windows Vista/7/8/10’. It could be updated in the future as well. Double click the downloaded file and click the ‘Next…’ button to complete the installation.

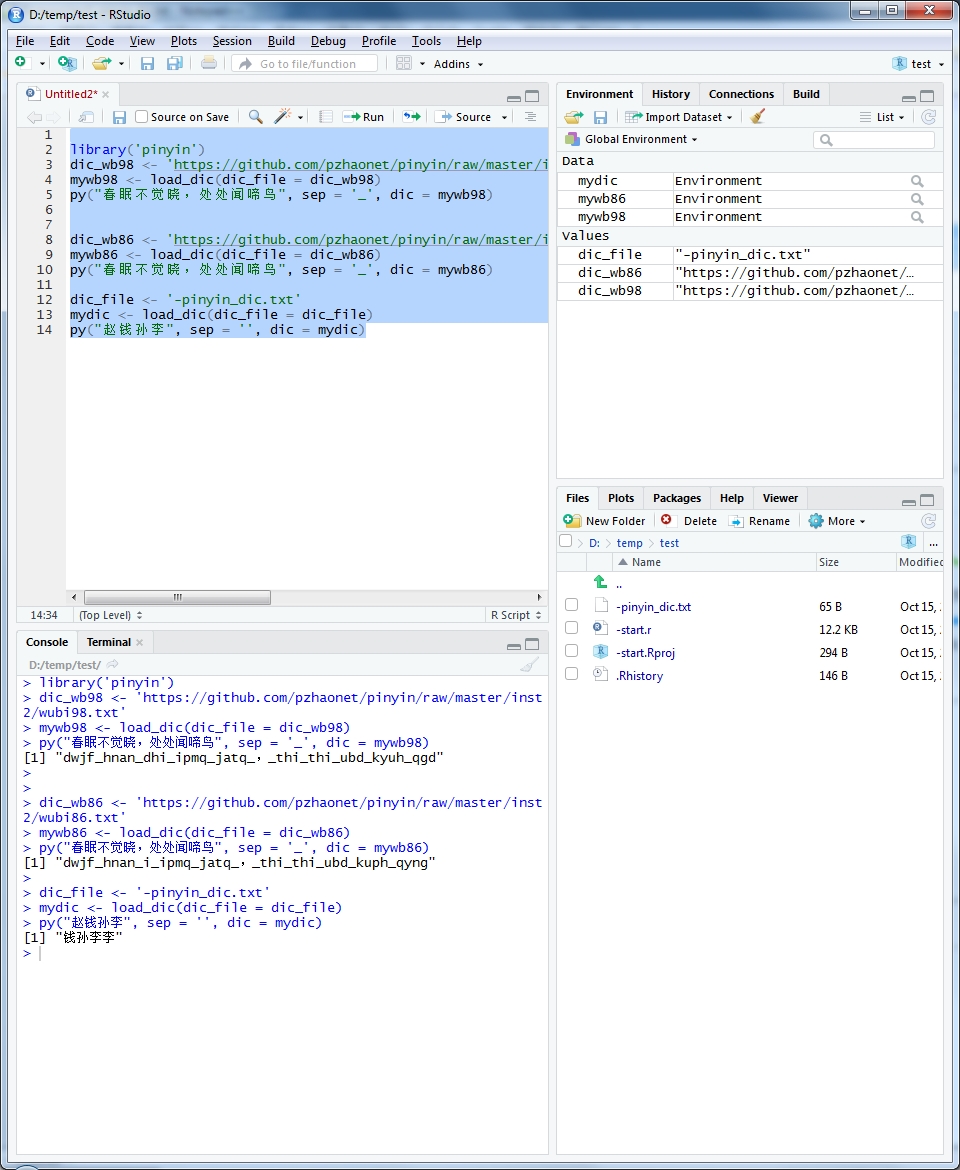

Fig. 1 shows how the RStudio user interface looks like.

Install and load ‘pinyin’

‘pinyin’ is available on CRAN. Users can install it in a normal way:

install.packages('pinyin')

or install the development version on GitHub:

devtools::install_github("pzhaonet/pinyin")

Before using it, users have to load the ‘pinyin’ package:

require('pinyin')

## Loading required package: pinyin

Functions in the ‘pinyin’ package

To list all the functions as well as their arguments by ‘pinyin’, users can run the following codes:

lsf.str("package:pinyin")

## bookdown2py : function (folder = "py", remove_curly_bracket = TRUE, other_replace = NULL,

## dic = NA)

## file.rename2py : function (folder = "py", dic = NA)

## file2py : function (folder = "py", backup = TRUE, sep = " ", other_replace = NULL,

## encoding = "UTF-8", dic = NA)

## load_dic : function (dic_file = NA, select = 1)

## pinyin : function ()

## py : function (char = "", sep = "_", other_replace = NULL, dic = pydic())

## pydic : function (method = c("quanpin", "tone", "toneless"), multi = FALSE,

## only_first_letter = FALSE, dic = c("pinyin", "pinyin2"))

The usages of the functions are briefly summarized in Fig.

Among them all, py() is the main function. Beginners can get a first impression from using it, which is described in the subsequent sections.

Convert a single Chinese character

The py() function converts a single Chinese character. Here is a simple example:

py('春')

## 春

## "chūn"

Got it? Congrats! You can read Chinese now!

This example is the easiest usage of ‘pinyin’.

Exercise 1: Go to a webpage (such as my blog) with Chinese characters. Copy a Chinese character and convert it into pinyin.

Convert multiple Chinese characters

The py() function can convert a character vector as well. Try this:

py(c('你', '好', '坏'))

## 你 好 坏

## "nǐ" "hāo" "huài"

It can convert a string like this:

py("你好坏")

## 你好坏

## "nǐ_hāo_huài"

You can see the difference between a character vector and a string.

Data scientists may have to process data frames more often. py() can convert data columns, which are actually vectors. Here is an example.

testd <- data.frame(stringsAsFactors=FALSE,

x1 = c('我', '一定', '是个', '天才'),

x2 = c('我', '确', '是个', '天才'))

testd$x1py <- py(testd$x1)

testd$x2py <- py(testd$x2)

testd

## x1 x2 x1py x2py

## 1 我 我 wǒ wǒ

## 2 一定 确 yī_dìnɡ què

## 3 是个 是个 shì_ɡàn shì_ɡàn

## 4 天才 天才 tiān_cái tiān_cái

Chinese is easy to learn, isn’t it?

Exercise 2: Go to a webpage with Chinese characters. Copy a Chinese sentence and convert it into pinyin.